Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

| Mohammad Reza Shah محمدرضا شاه | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah of Iran Light of the Aryans | |||||

Official portrait, 1973 | |||||

| Shah of Iran | |||||

| Reign | 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979 | ||||

| Coronation | 26 October 1967 | ||||

| Predecessor | Reza Shah | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished Ruhollah Khomeini (as supreme leader) | ||||

| Born | 26 October 1919 Tehran, Sublime State of Persia | ||||

| Died | 27 July 1980 (aged 60) Cairo, Egypt | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Alma mater | |||||

| House | Pahlavi | ||||

| Father | Reza Shah | ||||

| Mother | Tadj ol-Molouk | ||||

| Religion | Twelver Shia Islam | ||||

| Signature |  Persian signature  Latin signature | ||||

| Military service | |||||

| Branch/service | Imperial Iranian Army | ||||

| Years of service | 1936-1941 | ||||

| Rank | Captain | ||||

| Commands | Army's Inspection Department | ||||

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi[a] (26 October 1919 – 27 July 1980), commonly referred to in the Western world as Mohammad Reza Shah,[b] or simply the Shah, was the last monarch of Iran (Persia). He began ruling the Imperial State of Iran after succeeding his father, Reza Shah, in 1941 and remained in power until he was overthrown by the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which abolished the country's monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran. In 1967, he took up the title Shahanshah (lit. 'King of Kings'),[1] and also held several others, including Aryamehr (lit. 'Light of the Aryans') and Bozorg Arteshtaran (lit. 'Grand Army Commander'). He was the second and last ruling monarch of the Pahlavi dynasty to rule Iran. His dream of what he referred to as a "Great Civilization" (تمدن بزرگ) in Iran led to his leadership over rapid industrial and military modernization, as well as economic and social reforms.[2][3]

During World War II, the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran forced the abdication of Pahlavi's father, Reza Shah, whom he succeeded. During Pahlavi's reign, the British-owned oil industry was nationalized by the prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who had support from Iran's national parliament to do so; however, Mosaddegh was overthrown in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, which was carried out by the Iranian military under the aegis of the United Kingdom and the United States. Subsequently, the Iranian government centralized power under Pahlavi and brought foreign oil companies back into the country's industry through the Consortium Agreement of 1954.[4]

In 1963, Mohammad Reza introduced the White Revolution, a series of economic, social, and political reforms aimed at transforming Iran into a global power and modernizing the nation by nationalizing key industries and redistributing land. The regime also implemented Iranian nationalist policies establishing Cyrus the Great, the Cyrus Cylinder, and the Tomb of Cyrus the Great as popular symbols of Iran. In 1971, the Shah hosted the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire to honor and highlight the legacy of Achaemenid Empire. The Shah initiated major investments in infrastructure, subsidies and land grants for peasant populations, profit sharing for industrial workers, construction of nuclear facilities, nationalization of Iran's natural resources, and literacy programs which were considered some of the most effective in the world. Shah also instituted economic policy tariffs and preferential loans to Iranian businesses which sought to create an independent economy for the nation. Manufacturing of cars, appliances, and other goods in Iran increased substantially, leading to the creation of a new industrialist class insulated from threats of foreign competition. By the 1970s, Shah was seen as a master statesman and used his growing power to pass the 1973 Sale and Purchase Agreement. These reforms culminated in decades of sustained economic growth that would make Iran one of the fastest-growing economies among both the developed world and the developing world. During his 37-year-long rule, Iran spent billions of dollars' worth on industry, education, health, and military spending and enjoyed economic growth rates exceeding the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Likewise, the Iranian national income rose 423 times over, and the country saw an unprecedented rise in per capita income—which reached the highest level of any point in Iran's history—and high levels of urbanization. By 1977, Mohammad Reza's focus on defense spending, which he saw as a means to end foreign powers' intervention in the country, had culminated in the Iranian military standing as the world's fifth-strongest armed force.[5]

As political unrest grew throughout Iran in the late 1970s,[6] Mohammad Reza's position in the country was made untenable by the Jaleh Square massacre, in which the Iranian military killed and wounded dozens of protesters in Tehran,[7] and the Cinema Rex fire, an arson attack in Abadan that was erroneously blamed on the Iranian intelligence agency SAVAK. The 1979 Guadeloupe Conference saw Mohammad Reza's Western allies state that there was no feasible way to save the Iranian monarchy from being overthrown. The Shah ultimately left Iran for exile on 17 January 1979.[8] Although he had told some Western contemporaries that he would rather leave the country than fire on his own people,[9] estimates for the total number of deaths during the Islamic Revolution range from 540 to 2,000 (figures of independent studies) to 60,000 (figures of the Islamic government).[10] After formally abolishing the Iranian monarchy, Muslim cleric Ruhollah Khomeini assumed leadership as the Supreme Leader of Iran. Mohammad Reza died in exile in Egypt, where he had been granted political asylum by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat. Following his death, his son Reza Pahlavi declared himself as the new Shah of Iran in exile.

Early life, family and education

[edit]

Born in Tehran, in the Sublime State of Iran, to Reza Khan (later Reza Shah Pahlavi, first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty) and his second wife, Tadj ol-Molouk, Mohammad Reza was his father's eldest son and third of his eleven children. His father was of Mazandarani origin[11][12][13] and born in Alasht, Savadkuh County, Māzandarān Province. He was a Brigadier-General of the Persian Cossack Brigade, commissioned in the 7th Savadkuh Regiment, who served in the Anglo-Persian War in 1856.[14] Mohammad Reza's mother was a Muslim immigrant from Georgia (then part of the Russian Empire),[15] whose family had emigrated to mainland Iran after Iran was forced to cede all of its territories in the Caucasus following the Russo-Persian Wars several decades prior.[16] She was of Azerbaijani origin, being born in Baku, Russian Empire (now Azerbaijan).

Mohammad Reza was born with his twin sister, Ashraf; however, he, Ashraf, his siblings Shams and Ali Reza, and his older half-sister, Fatimeh, were not royalty by birth, as their father did not become Shah until 1925. Nevertheless, Reza Khan was always convinced that his sudden quirk of good fortune had commenced in 1919 with the birth of his son, who was dubbed khoshghadam ("bird of good omen").[17] Like most Iranians at the time, Reza Khan did not have a surname. After the 1921 Persian coup d'état which saw the deposal of Ahmad Shah Qajar, Reza Khan was informed that he would need a surname for his house. This led him to pass a law ordering all Iranians to take a surname; he chose for himself the surname Pahlavi, which is the name for the Middle Persian language, itself derived from Old Persian.[18] At his father's coronation on 24 April 1926, Mohammad Reza was proclaimed Crown Prince.[18][19]

Family

[edit]Mohammad Reza described his father in his book Mission for My Country as "one of the most frightening men" he had ever known, depicting Reza Khan as a dominating man with a violent temper.[20] A tough, fierce, and very ambitious soldier who became the first Persian to command the elite Russian-trained Cossack Brigade, Reza Khan liked to kick subordinates in the groin who failed to follow his orders. Growing up under his shadow, Mohammad Reza was a deeply scared and insecure boy who lacked self-confidence, according to Iranian-American historian Abbas Milani.[21]

Reza Khan believed if fathers showed love for their sons, it caused homosexuality later in life, so to ensure his favourite son was heterosexual, he denied him love and affection when he was young, though he later became more affectionate toward the Crown Prince when he was a teenager.[22] Reza Khan always addressed his son as shoma ("sir") and refused to use the more informal tow ("you"), and in turn was addressed by his son using the same formality.[23] The Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński observed in his book Shah of Shahs that looking at old photographs of Reza Khan and his son, he was struck by how self-confident and assured Reza Khan appeared in his uniform, while Mohammad Reza appeared nervous and jittery in his uniform standing next to his father.[24]

In the 1930s, Reza Khan was an outspoken admirer of Adolf Hitler, less because of Hitler's racism and anti-Semitism and more because he had risen from an undistinguished background, much like Reza Khan, to become a notable leader of the 20th century.[25] Reza Khan often impressed on his son his belief that history was made by great men such as himself, and that a real leader is an autocrat.[25] Reza Khan was a large, muscular man who stood at over 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m), leading his son to liken him to a mountain. Throughout his life, Mohammad Reza was obsessed with height and stature, wearing elevator shoes to make himself look taller than he really was, often boasting that Iran's highest mountain Mount Damavand was higher than any peak in Europe or Japan, and proclaiming that he was always most attracted to tall women.[26] As Shah, Mohammad Reza constantly disparaged his father in private, calling him a thuggish Cossack who achieved nothing as Shah. In fact, he almost airbrushed his father out of history during his reign, to the point of implying the House of Pahlavi began its rule in 1941 rather than 1925.[27]

Mohammad Reza's mother, Tadj ol-Molouk, was an assertive woman who was also very superstitious. She believed that dreams were messages from another world, sacrificed lambs to bring good fortune and scare away evil spirits, and clad her children with protective amulets to ward off the power of the evil eye.[28] Tadj ol-Molouk was the main emotional support to her son, and she cultivated a belief in him that destiny had chosen him for great things, which the soothsayers she consulted had interpreted her dreams as proving.[29] Mohammad Reza grew up surrounded by women, as the main influences on him were his mother, his older sister Shams, and his twin sister Ashraf, leading the American psychoanalyst and political economist Marvin Zonis to conclude that it was "from women, and apparently from women alone" that the future Shah "received whatever psychological nourishment he was able to get as a child".[30] Traditionally, male children were considered preferable to females, and as a boy, Mohammad Reza was often spoiled by his mother and sisters.[30] Mohammad Reza was very close to his twin sister Ashraf, who commented, "It was this twinship and this relationship with my brother that would nourish and sustain me throughout my childhood ... No matter how I would reach out in the years to come—sometimes even desperately—to find an identity and a purpose of my own, I would remain inextricably tied to my brother ... always, the center of my existence was, and is, Mohammad Reza".[31]

After becoming Crown Prince, Mohammad Reza was taken away from his mother and sisters to be given a "manly education" by officers selected by his father, who also ordered that everyone, including his mother and siblings, were to address the Crown Prince as "Your Highness".[23] According to Zonis, the result of his contradictory upbringing by a loving, if possessive and superstitious, mother and an overbearing martinet father was to make Mohammad Reza "a young man of low self-esteem who masked his lack of self-confidence, his indecisiveness, his passivity, his dependency and his shyness with masculine bravado, impulsiveness, and arrogance". This made him into a person of marked contradictions, Zonis claims, as the Crown Prince was "both gentle and cruel, withdrawn and active, dependent and assertive, weak and powerful".[32]

Education

[edit]

By the time Mohammad Reza turned 11, his father deferred to the recommendation of Abdolhossein Teymourtash, the Minister of Court, to dispatch his son to Institut Le Rosey, a Swiss boarding school, for further studies. Mohammad Reza left Iran for Switzerland on 7 September 1931.[33] On his first day as a student at Le Rosey, the Crown Prince antagonised a group of his fellow students by demanding that they all stand to attention as he walked past, just as everybody did back in Iran. In response, one of the American students beat him up, and he swiftly learned to accept that people would not respect him in Switzerland in the way he was accustomed to at home.[34] As a student, Mohammad Reza played competitive football, but school records indicate that his principal problem as a player was his "timidity", as the Crown Prince was afraid to take risks.[35] He was educated in French at Le Rosey, and his time there left Mohammad Reza with a lifelong love of all things French.[36] In articles he wrote in French for the student newspaper in 1935 and 1936, Mohammad Reza praised Le Rosey for broadening his mind and introducing him to European civilisation.[35]

Mohammad Reza was the first Iranian prince in line for the throne to be sent abroad to attain a foreign education and remained there for the next four years before returning to obtain his high school diploma in Iran in 1936. After returning to the country, the Crown Prince was registered at the local military academy in Tehran where he remained enrolled until 1938, graduating as a Second Lieutenant. Upon graduating, Mohammad Reza was quickly promoted to the rank of Captain, a rank which he kept until he became Shah. During college, the young prince was appointed Inspector of the Army and spent three years travelling across the country, examining both civil and military installations.[19][37]

Mohammad Reza spoke English, French, and German fluently, in addition to his native language of Persian.[38]

During his time in Switzerland, Mohammad Reza befriended his teacher Ernest Perron, who introduced him to French poetry, and under his influence, Chateaubriand and Rabelais became his "favorite French authors".[39] The Crown Prince liked Perron so much that when he returned to Iran in 1936, he brought Perron back with him, installing his best friend in the Marble Palace.[40] Perron lived in Iran until his death in 1961, and as the best friend of Mohammad Reza, was a man of considerable behind-the-scenes power.[41] After the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979, a best-selling book was published by the new regime, Ernest Perron, the Husband of the Shah of Iran, by Mohammad Pourkian, alleging a homosexual relationship between the Shah and Perron. Even today, this remains the official interpretation of their relationship by the Islamic Republic of Iran.[42] Marvin Zonis described the book as long on assertions and short on evidence of a homosexual relationship between the two, noting that all of the Shah's courtiers rejected the claim that Perron was the Shah's lover. He argued that the strong-willed Reza Khan, who was very homophobic, would not have allowed Perron to move into the Marble Palace in 1936 if he believed Perron was his son's lover.[43]

Rise to power

[edit]First marriage

[edit]

One of the main initiatives of Iranian and Turkish foreign policy had been the Saadabad Pact of 1937, an alliance bringing together Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan, with the intent of creating a Muslim bloc that, it was hoped, would deter any aggressors. President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of Turkey suggested to his friend Reza Khan during the latter's visit that a marriage between the Iranian and Egyptian courts would be beneficial for the two countries and their dynasties, as it might lead to Egypt joining the Saadabad pact.[44] Dilawar Princess Fawzia of Egypt (5 November 1921 – 2 July 2013) was daughter of King Fuad I of Egypt and Nazli Sabri and sister of King Farouk I of Egypt. In line with Atatürk's suggestion, Mohammad Reza and the Egyptian Princess Fawzia were married on 15 March 1939 in the Abdeen Palace in Cairo.[44] Reza Shah did not participate in the ceremony.[44] During his visit to Egypt, Mohammad Reza was greatly impressed with the grandeur of the Egyptian court as he visited the various palaces built by Isma'il Pasha, aka "Isma'il the Magnificent", the famously free-spending Khedive of Egypt, and resolved that Iran needed similarly grandiose palaces to match them.[45]

Mohammad Reza's marriage to Fawzia produced one child, Princess Shahnaz Pahlavi (born 27 October 1940). Their marriage was not a happy one, as the Crown Prince was openly unfaithful, often being seen driving around Tehran in one of his expensive cars with one of his girlfriends.[46] Additionally, Mohammad Reza's dominating and possessive mother saw her daughter-in-law as a rival to her son's love, and took to humiliating Princess Fawzia, whose husband sided with his mother.[46] A quiet, shy woman, Fawzia described her marriage as miserable, feeling very much unwanted and unloved by the Pahlavi family and longing to return to Egypt.[46] In his 1961 book Mission For My Country, Mohammad Reza wrote that the "only happy light moment" of his entire marriage to Fawzia was the birth of his daughter.[47]

Anglo-Soviet invasion and deposition of his father Reza Shah

[edit]

Meanwhile, in the midst of World War II in 1941, Nazi Germany began Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union, breaking the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. This had a major impact on Iran, which had declared neutrality in the conflict.[48] In the summer of 1941, Soviet and British diplomats passed on numerous messages warning that they regarded the presence of Germans administering the Iranian state railroads as a threat, implying war if the Germans were not dismissed.[49] Britain wished to ship arms to the Soviet Union via Iranian railroads, and statements from the German managers of the Iranian railroads that they would not cooperate made both the Soviets and British insistent that the Germans Reza Khan had hired had to be sacked at once.[49] As his father's closest advisor, the Crown Prince Mohammad Reza did not see fit to raise the issue of a possible Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, blithely assuring his father that nothing would happen.[49] The Iranian-American historian Abbas Milani wrote about the relationship between the Reza Khan and the Crown Prince at the time, noting, "As his father's now constant companion, the two men consulted on virtually every decision".[50]

Later that year, British and Soviet forces occupied Iran in a military invasion, forcing Reza Shah to abdicate.[51] On 25 August 1941, British and Australian naval forces attacked the Persian Gulf while the Soviet Union conducted a land invasion from the north. On the second day of the invasion, with the Soviet air force bombing Tehran, Mohammad Reza was shocked to see the Iranian military simply collapse, with thousands of terrified officers and men all over Tehran taking off their uniforms in order to desert and run away, despite having not yet seen combat.[52] Reflecting the panic, a group of senior Iranian generals called the Crown Prince to receive his blessing to hold a meeting to discuss how best to surrender.[50] When Reza Khan learned of the meeting, he flew into a rage and attacked one of his generals, Ahmad Nakhjavan, striking him with his riding crop, tearing off his medals, and nearly personally executing him before his son persuaded him to have the general court-martialed instead.[50] The collapse of the Iranian military that his father had worked so hard to build humiliated his son, who vowed that he would never see Iran defeated like that again, foreshadowing the future Shah's later obsession with military spending.[52]

Ascension to the throne

[edit]

On 16 September 1941, Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Foroughi and Foreign Minister Ali Soheili attended a special session of parliament to announce the resignation of Reza Shah and that Mohammad Reza was to replace him. The next day, at 4:30 pm, Mohammad Reza took the oath of office and was received warmly by parliamentarians. On his way back to the palace, the streets filled with people welcoming the new Shah jubilantly, seemingly more enthusiastic than the Allies would have liked.[53] The British would have liked to put a Qajar back on the throne, but the principal Qajar claimant to the throne was Prince Hamid Mirza, an officer in the Royal Navy who did not speak Persian, so the British were forced to accept Mohammad Reza as Shah.[54] The main Soviet interest in 1941 was to ensure political stability to ensure Allied supplies, which meant accepting Mohammad Reza's ascension to the throne. Subsequent to his succession as king, Iran became a major conduit for British and, later, American aid to the USSR during the war. This massive supply route became known as the Persian Corridor.[55]

Much of the credit for orchestrating a smooth transition of power from the King to the Crown Prince was due to the efforts of Mohammad Ali Foroughi.[56] Suffering from angina, a frail Foroughi was summoned to the Palace and appointed prime minister when Reza Shah feared the end of the Pahlavi dynasty once the Allies invaded Iran in 1941.[57] When Reza Shah sought his assistance to ensure that the Allies would not put an end to the Pahlavi dynasty, Foroughi put aside his adverse personal sentiments for having been politically sidelined since 1935. The Crown Prince confided in amazement to the British minister that Foroughi "hardly expected any son of Reza Shah to be a civilized human being",[57] but Foroughi successfully derailed thoughts by the Allies to undertake a more drastic change in the political infrastructure of Iran.[58]

A general amnesty was issued two days after Mohammad Reza's accession to the throne on 19 September 1941. All political personalities who had suffered disgrace during his father's reign were rehabilitated, and the forced unveiling policy inaugurated by his father in 1935 was overturned. Despite the young king's enlightened decisions, the British minister in Tehran reported to London that "the young Shah received a fairly spontaneous welcome on his first public experience, possibly rather [due] to relief at the disappearance of his father than to public affection for himself". During his early days as Shah, Mohammad Reza lacked self-confidence and spent most of his time with Perron writing poetry in French.[59]

In 1942, Mohammad Reza met Wendell Willkie, the Republican candidate for the U.S. presidency in the 1940 election who was now on a world tour to promote his "one world" policy. Willkie took the Shah flying for the first time.[60] The prime minister, Ahmad Qavam, had advised the Shah against flying with Willkie, saying he had never met a man with a worse flatulence problem, but the Shah took his chances.[60] Mohammad Reza told Willkie that when he was flying that he "wanted to stay up indefinitely".[60] Enjoying flight, Mohammad Reza hired the American pilot Dick Collbarn to teach him how to fly. Upon arriving at the Marble Palace, Collbarn noted that "the Shah must have twenty-five custom-built cars ... Buicks, Cadillacs, six Rolls-Royces, a Mercedes".[60] During the Tehran conference with the Allied forces in 1943, the Shah was humiliated when he met Joseph Stalin, who visited him in the Marble Palace and did not allow the Shah's bodyguards to be present, with the Red Army alone guarding them.[61]

Opinion of his father's rule

[edit]Despite his public professions of admiration in later years, Mohammad Reza had serious misgivings about not only the coarse and roughshod political means adopted by his father, but also his unsophisticated approach to affairs of state. The young Shah possessed a decidedly more refined temperament, and amongst the unsavory developments that "would haunt him when he was king" were the political disgrace brought by his father on Teymourtash, the dismissal of Foroughi by the mid-1930s, and Ali Akbar Davar's suicide in 1937.[62] An even more significant decision that cast a long shadow was the disastrous and one-sided agreement his father had negotiated with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) in 1933, one which compromised the country's ability to receive more favourable returns from oil extracted from the country.

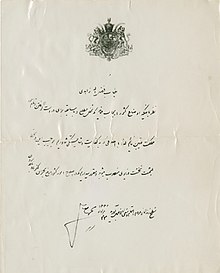

Relationship with his exiled father

[edit]Mohammad Reza expressed concern for his exiled father, who had previously complained to the British governor of Mauritius that living on the island was both a climatic and social prison. Attentively following his life in exile, Mohammad Reza would object to his father's treatment to the British at any opportunity. The two sent letters to one another, although delivery was often delayed, and Mohammad Reza commissioned his friend, Ernest Perron, to hand-deliver a taped message of love and respect to his father, bringing back with him a recording of his voice:[63]

My dear son, since the time I resigned in your favour and left my country, my only pleasure has been to witness your sincere service to your country. I have always known that your youth and your love of the country are vast reservoirs of power on which you will draw to stand firm against the difficulties you face and that, despite all the troubles, you will emerge from this ordeal with honour. Not a moment passes without my thinking of you and yet the only thing that keeps me happy and satisfied is the thought that you are spending your time in the service of Iran. You must remain always aware of what goes on in the country. You must not succumb to advice that is self-serving and false. You must remain firm and constant. You must never be afraid of the events that come your way. Now that you have taken on your shoulders this heavy burden in such dark days, you must know that the price to be paid for the slightest mistake on your part may be our twenty years of service and our family's name. You must never yield to anxiety or despair; rather, you must remain calm and so strongly rooted in your place that no power may hope to move the constancy of your will.[64]

Onset of the Cold War

[edit]

In 1945–46, the main issue in Iranian politics was the Soviet-sponsored separatist government in Iranian Azerbaijan and Kurdistan, which greatly alarmed the Shah. He repeatedly clashed with his prime minister Ahmad Qavam, whom he viewed as too pro-Soviet.[65] At the same time, the growing popularity of the communist Tudeh Party worried Mohammad Reza, who felt there was a serious possibility of them leading a coup.[66] In June 1946, Mohammad Reza was relieved when the Red Army pulled out of Iran.[67] In a letter to the Azerbaijani Communist leader Ja'far Pishevari, Stalin wrote that he had to pull out of Iran, as otherwise the Americans would not pull out of China, and he wanted to assist the Chinese Communists in their civil war against the Kuomintang.[68] However, the Pishevari regime remained in power in Tabriz, Azerbaijan, and Mohammad Reza sought to undercut Qavam's attempts to make an agreement with Pishevari as way of getting rid of both.[69] On 11 December 1946, the Iranian Army, led by the Shah in person, entered Iranian Azerbaijan and the Pishevari regime collapsed with little resistance, with most of the fighting occurring between ordinary people who attacked functionaries of the Pishevari that had treated them brutally.[69] In his statements at the time and later, Mohammad Reza credited his easy success in Azerbaijan to his "mystical power".[70] Knowing Qavam's penchant for corruption, the Shah used that issue as a reason to sack him.[71] By this time, the Shah's wife Fawzia had returned to Egypt, and despite efforts to have King Farouk persuade her to return to Iran, she refused to go, which led Mohammad Reza to divorce her on 17 November 1948.[72]

By now a qualified pilot, Mohammad Reza was fascinated with flying and the technical details of aeroplanes, and any insult to him was always an attempt to "clip [his] wings". Mohammad Reza directed more money to the Imperial Iranian Air Force than any branch of the armed forces, and his favourite uniform was that of the Marshal of the Imperial Iranian Air Force.[73] Marvin Zonis wrote that Mohammad Reza's obsession with flying reflected an Icarus complex, also known as "ascensionism", a form of narcissism based on "a craving for unsolicited attention and admiration" and the "wish to overcome gravity, to stand erect, to grow tall ... to leap or swing into the air, to climb, to rise, to fly".[74]

Mohammad Reza often spoke of women as sexual objects who existed only to gratify him, and during a 1973 interview with Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, she vehemently objected to his attitudes towards women.[75] As a regular visitor to the nightclubs of Italy, France, and the United Kingdom, Mohammad Reza was linked romantically to several actresses, including Gene Tierney, Yvonne De Carlo, and Silvana Mangano.[76]

At least two unsuccessful assassination attempts were made against the young Shah. On 4 February 1949, he attended an annual ceremony to commemorate the founding of Tehran University.[77] At the ceremony, gunman Fakhr-Arai fired five shots at him at a range of about three metres. Only one of the shots hit the king, grazing his cheek. The gunman was instantly shot by nearby officers. After an investigation, Fakhr-Arai was declared a member of the communist Tudeh Party,[78] which was subsequently banned.[79] However, there is evidence that the would-be assassin was not a Tudeh member but a religious fundamentalist member of Fada'iyan-e Islam.[76][80] The Tudeh were nonetheless blamed and persecuted.[81]

The Shah's second wife was Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary, a half-German, half-Iranian woman and the only daughter of Khalil Esfandiary-Bakhtiary, Iranian Ambassador to West Germany, and his wife Eva Karl. She was introduced to the Shah by Forough Zafar Bakhtiary, a close relative of Soraya's, via a photograph taken by Goodarz Bakhtiary, in London, per Forough Zafar's request. They married on 12 February 1951,[44] when Soraya was 18, according to the official announcement. However, it was rumoured that she was actually 16, the Shah being 32.[82] As a child, she was tutored and brought up by Frau Mantel, and hence lacked proper knowledge of Iran, as she herself admitted in her personal memoirs, stating, "I was a dunce—I knew next to nothing of the geography, the legends of my country, nothing of its history, nothing of Muslim religion".[65]

Nationalization of oil and 1953 Iranian coup d'état

[edit]

By the early 1950s, the political crisis brewing in Iran commanded the attention of British and American policy leaders. Following the 1950 Iranian legislative election, Mohammad Mosaddegh was elected prime minister in 1951. He was committed to nationalising the Iranian petroleum industry controlled by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) (formerly the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, or APOC).[83] Under the leadership of Mosaddegh and his nationalist movement, the Iranian parliament unanimously voted to nationalise the oil industry, thus shutting out the immensely profitable AIOC, which was a pillar of Britain's economy and provided it political clout in the region.[84]

At the start of the confrontation, American political sympathy with Iran was forthcoming from the Truman Administration.[85] In particular, Mosaddegh was buoyed by the advice and counsel he was receiving from the American Ambassador in Tehran, Henry F. Grady. However, eventually American decision-makers lost their patience, and by the time the Republican administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower entered office, fears that communists were poised to overthrow the government became an all-consuming concern. These concerns were later dismissed as "paranoid" in retrospective commentary on the coup from U.S. government officials. Shortly prior to the 1952 presidential election in the United States, the British government invited Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer Kermit Roosevelt Jr., to London to propose collaboration on a secret plan to force Mosaddegh from office.[86] This would be the first of three "regime change" operations led by CIA director Allen Dulles (the other two being the successful CIA-instigated 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état and the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba).

Under the direction of Roosevelt, the American CIA and British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) funded and led a covert operation to depose Mosaddegh with the help of military forces disloyal to the government. Referred to as Operation Ajax,[87] the plot hinged on orders signed by Mohammad Reza to dismiss Mosaddegh as prime minister and replace him with General Fazlollah Zahedi, a choice agreed on by the British and Americans.[88][89][90]

Before the attempted coup, the American Embassy in Tehran reported that Mosaddegh's popular support remained robust. The Prime Minister requested direct control of the army from the Majlis. Given the situation, alongside the strong personal support of Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden for covert action, the American government gave the go-ahead to a committee, attended by the Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles, Kermit Roosevelt Jr., Henderson,[who?] and Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson. Kermit Roosevelt Jr. returned to Iran on 13 July 1953, and again on 1 August 1953, in his first meeting with the king. A car picked him up at midnight and drove him to the palace. He lay down on the seat and covered himself with a blanket as guards waved his driver through the gates. The Shah got into the car and Roosevelt explained the mission. The CIA bribed him with $1 million in Iranian currency, which Roosevelt had stored in a large safe—a bulky cache, given the then-exchange rate of 1,000 rial to 15 US dollars.[91]

Meanwhile, the Communists staged massive demonstrations to hijack Mosaddegh's initiatives, and the United States actively plotted against him. On 16 August 1953, the right wing of the Army attacked. Armed with an order by the Shah, it appointed General Fazlollah Zahedi as prime minister. A coalition of mobs and retired officers close to the Palace executed this coup d'état. They failed dismally and the Shah fled the country to Baghdad, and then to Rome. Ettelaat, the nation's largest daily newspaper, and its pro-Shah publisher, Abbas Masudi, criticised him, calling the defeat "humiliating".[92]

During the Shah's time in Rome, a British diplomat reported that the monarch spent most of his time in nightclubs with Queen Soraya or his latest mistress, writing, "He hates taking decisions and cannot be relied on to stick to them when taken. He has no moral courage and succumbs easily to fear".[93] To get him to support the coup, his twin sister Princess Ashraf—who was much tougher than him and publicly questioned his manhood several times—visited him on 29 July 1953 to berate him into signing a decree dismissing Mossaddegh.[94]

In the days leading up to the second coup attempt, the Communists turned against Mosaddegh. Opposition against him grew tremendously. They roamed Tehran, raising red flags and pulling down statues of Reza Shah. This was rejected by conservative clerics like Kashani and National Front leaders like Hossein Makki, who sided with the king. On 18 August 1953, Mosaddegh defended the government against this new attack. Tudeh partisans were clubbed and dispersed.[95] The Tudeh party had no choice but to accept defeat.

In the meantime, according to the CIA plot, Zahedi appealed to the military, claimed to be the legitimate prime minister and charged Mosaddegh with staging a coup by ignoring the Shah's decree. Zahedi's son Ardeshir acted as the contact between the CIA and his father. On 19 August 1953, pro-Shah partisans—bribed with $100,000 in CIA funds—finally appeared and marched out of south Tehran into the city centre, where others joined in. Gangs with clubs, knives, and rocks controlled the streets, overturning Tudeh trucks and beating up anti-Shah activists. As Roosevelt was congratulating Zahedi in the basement of his hiding place, the new Prime Minister's mobs burst in and carried him upstairs on their shoulders. That evening, Henderson suggested to Ardashir that Mosaddegh not be harmed. Roosevelt gave Zahedi US$900,000 left from Operation Ajax funds.[96]

After his brief exile in Italy, the Shah returned to Iran, this time through the successful second coup attempt. The deposed Mosaddegh was arrested and tried, with the king intervening and commuting his sentence to three years,[97] to be followed by life in internal exile. Zahedi was installed to succeed Mosaddegh.[98] Although Mohammad Reza returned to power, he never extended the elite status of the court to the technocrats and intellectuals who emerged from Iranian and Western universities. Indeed, his system irritated the new classes, for they were barred from partaking in real power.[99]

Self-assertion: from figurehead monarch to effective authoritarian

[edit]

In the aftermath of the 1953 coup d'état, Mohammad Reza was widely viewed as a figurehead monarch, and General Fazlollah Zahedi, the Prime Minister, saw himself and was viewed by others as the "strong man" of Iran.[100] Mohammad Reza feared that history would repeat itself, remembering how his father was a general who had seized power in a coup d'état in 1921 and deposed the last Qajar shah in 1925, and his major concern in the years 1953–55 was to neutralise Zahedi.[101] American and British diplomats in their reports back to Washington and London in the 1950s were openly contemptuous of Mohammad Reza's ability to lead, calling the Shah a weak-willed and cowardly man who was incapable of making a decision.[101] The contempt in which the Shah was held by Iranian elites led to a period in the mid-1950s where the elite displayed fissiparous tendencies, feuding amongst themselves now that Mossadegh had been overthrown, which ultimately allowed Mohammad Reza to play off various factions in the elite to assert himself as the nation's leader.[101]

The very fact that Mohammad Reza was considered a coward and insubstantial turned out be an advantage as the Shah proved to be an adroit politician, playing off the factions in the elite and the Americans against the British with the aim of being an autocrat in practice as well as in theory.[101] Supporters of the banned National Front were persecuted, but in his first important decision as leader, Mohammad Reza intervened to ensure most of the members of the National Front brought to trial, such as Mosaddegh himself, were not executed as many had expected.[102] Many in the Iranian elite were openly disappointed that Mohammad Reza did not conduct the expected bloody purge and hang Mosaddegh and his followers as they had wanted and expected.[102] In 1954, when twelve university professors issued a public statement criticising the 1953 coup, all were dismissed from their jobs, but in the first of his many acts of "magnanimity" towards the National Front, Mohammad Reza intervened to have them reinstated.[103] Mohammad Reza tried very hard to co-opt the supporters of the National Front by adopting some of their rhetoric and addressing their concerns, for example declaring in several speeches his concerns about the Third World economic conditions and poverty which prevailed in Iran, a matter that had not much interested him before.[104]

Mohammad Reza was determined to copy Mosaddegh, who had won popularity by promising broad socio-economic reforms, and wanted to create a mass powerbase as he did not wish to depend upon the traditional elites, who only wanted him as a legitimising figurehead.[102] In 1955, Mohammad Reza dismissed General Zahedi from his position as prime minister and appointed his archenemy, the technocrat Hossein Ala' as prime minister, whom he in turn dismissed in 1957.[105] Starting in 1955, Mohammad Reza began to quietly cultivate left-wing intellectuals, many of whom had supported the National Front and some of whom were associated with the banned Tudeh party, asking them for advice about how best to reform Iran.[106] It was during this period that Mohammad Reza began to embrace the image of a "progressive" Shah, a reformer who would modernise Iran, who attacked in his speeches the "reactionary" and "feudal" social system that was retarding progress, bring about land reform and give women equal rights.[106]

Determined to rule as well as reign, it was during the mid 1950s that Mohammad Reza started to promote a state cult around Cyrus the Great, portrayed as a great Shah who had reformed the country and built an empire with obvious parallels to himself.[106] Alongside this change in image, Mohammad Reza started to speak of his desire to "save" Iran, a duty that he claimed he had been given by God, and promised that under his leadership Iran would reach a Western standard of living in the near future.[107] During this period, Mohammad Reza sought the support of the ulema, and resumed the traditional policy of persecuting those Iranians who belonged to the Baháʼí Faith, allowing the chief Baháʼí temple in Tehran to be razed in 1955 and bringing in a law banning the Baháʼí from gathering together in groups.[107] A British diplomat reported in 1954 that Reza Khan "must have been spinning in his grave at Rey. To see the arrogance and effrontery of the mullahs once again rampant in the holy city! How the old tyrant must despise the weakness of his son, who allowed these turbulent priests to regain so much of their reactionary influence!"[107] By this time, the Shah's marriage was under strain as Queen Soraya complained about the power of Mohammad Reza's best friend Ernest Perron, whom she called a "shetun" and a "limping devil".[108] Perron was a man much resented for his influence on Mohammad Reza and was often described by enemies as a "diabolical" and "mysterious" character, whose position was that of a private secretary, but who was one of the Shah's closest advisors, holding far more power than his job title suggested.[109]

In a 1957 study compiled by the U.S. State Department, Mohammad Reza was praised for his "growing maturity" and no longer needing "to seek advice at every turn" as the previous 1951 study had concluded.[110] On 27 February 1958, a military coup to depose the Shah led by General Valiollah Gharani was thwarted, which led to a major crisis in Iranian-American relations when evidence emerged that associates of Gharani had met American diplomats in Athens, which the Shah used to demand that henceforward no American officials could meet with his opponents.[111] Another issue in Iranian-American relations was Mohammad Reza's suspicion that the United States was insufficiently committed to Iran's defense, observing that the Americans refused to join the Baghdad Pact, and military studies had indicated that Iran could only hold out for a few days in the event of a Soviet invasion.[112]

In January 1959, the Shah began negotiations on a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, which he claimed to have been driven to by a lack of American support.[113] After receiving a mildly threatening letter from President Eisenhower warning him against signing the treaty, Mohammad Reza chose not to sign, which led to a major Soviet propaganda effort calling for his overthrow.[114] Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev ordered Mohammad Reza assassinated.[115] A sign of Mohammad Reza's power came in 1959 when a British company won a contract with the Iranian government that was suddenly cancelled and given to Siemens instead.[116] An investigation by the British embassy soon uncovered the reason why: Mohammad Reza wanted to bed the wife of the Siemens sales agent for Iran, and the Siemens agent had consented to allowing his wife to sleep with the Shah in exchange for winning back the contract that he had just lost.[116] On 24 July 1959, Mohammad Reza gave Israel de facto recognition by allowing an Israeli trade office to be opened in Tehran that functioned as a de facto embassy, a move that offended many in the Islamic world.[117] When Eisenhower visited Iran on 14 December 1959, Mohammad Reza told him that Iran faced two main external threats: the Soviet Union to the north and the new pro-Soviet revolutionary government in Iraq to the west. This led him to ask for vastly increased American military aid, saying his country was a front-line state in the Cold War that needed as much military power as possible.[117]

The Shah and Soraya's marriage ended in 1958 when it became apparent that, even with help from medical doctors, she could not bear children. Soraya later told The New York Times that the Shah had no choice but to divorce her, and that he was heavy-hearted about the decision.[118] However, even after the marriage, it is reported that the Shah still had great love for Soraya, and it is reported that they met several times after their divorce and that she lived her post-divorce life comfortably as a wealthy lady, even though she never remarried;[119] being paid a monthly salary of about $7,000 from Iran.[120] Following her death in 2001 at the age of 69 in Paris, an auction of the possessions included a three-million-dollar Paris estate, a 22.37-carat diamond ring and a 1958 Rolls-Royce.[121]

Pahlavi subsequently indicated his interest in marrying Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy, a daughter of the deposed Italian king, Umberto II. Pope John XXIII reportedly vetoed the suggestion. In an editorial about the rumours surrounding the marriage of a "Muslim sovereign and a Catholic princess", the Vatican newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, considered the match "a grave danger",[122] especially considering that under the 1917 Code of Canon Law a Roman Catholic who married a divorced person would be automatically, and could be formally, excommunicated.

In the 1960 U.S. presidential election, the Shah had favoured the Republican candidate, incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon, whom he had first met in 1953 and rather liked, and according to the diary of his best friend Asadollah Alam, Mohammad Reza contributed money to the 1960 Nixon campaign.[123] Relations with the victor of the 1960 election, the Democrat John F. Kennedy, were not friendly.[123] In an attempt to mend relations after Nixon's defeat, Mohammad Reza sent General Teymur Bakhtiar of SAVAK to meet Kennedy in Washington on 1 March 1961.[124] From Kermit Roosevelt, Mohammad Reza learned that Bakhtiar, during his trip to Washington, had asked the Americans to support a coup he was planning, which greatly increased the Shah's fears about Kennedy.[124] On 2 May 1961, a teacher's strike involving 50,000 people began in Iran, which Mohammad Reza believed was the work of the CIA.[125] Mohammad Reza had to sack his prime minister Jafar Sharif-Emami and give in to the teachers after learning that the Army probably would not fire on the demonstrators.[126] In 1961, Bakhtiar was dismissed as chief of SAVAK and expelled from Iran in 1962 following a clash between demonstrating university students and the army on 21 January 1962 that left three dead.[127] In April 1962, when Mohammad Reza visited Washington, he was met with demonstrations by Iranian students at American universities, which he believed were organised by U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the President's brother and the leading anti-Pahlavi voice in the Kennedy administration.[128] Afterwards, Mohammad Reza visited London. In a sign of the changed dynamics in Anglo-Iranian relations, the Shah took offence when he was informed he could join Queen Elizabeth II for a dinner at Buckingham Palace that was given in somebody else's honour, insisting successfully he would have dinner with the Queen only when given in his own honour.[128]

Mohammad Reza's first major clash with Ayatollah Khomeini occurred in 1962, when the Shah changed the local laws to allow Iranian Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Baha'i to take the oath of office for municipal councils using their holy books instead of the Koran.[129] Khomeini wrote to the Shah to say this was unacceptable and that only the Koran could be used to swear in members of the municipal councils regardless of what their religion was, writing that he heard "Islam is not indicated as a precondition for standing for office and women are being granted the right to vote...Please order all laws inimical to the sacred and official faith of the country to be eliminated from government policies."[129] The Shah wrote back, addressing Khomeini as Hojat-al Islam rather than as Ayatollah, declining his request.[129] Feeling pressure from demonstrations organised by the clergy, the Shah withdrew the offending law, but it was reinstated with the White Revolution of 1963.[130]

Middle years

[edit]The White Revolution

[edit]

Conflict with Islamists

[edit]In 1963, Mohammad Reza launched the White Revolution, a series of far-reaching reforms, which caused much opposition from the religious scholars. They were enraged that the referendum approving of the White Revolution in 1963 allowed women to vote, with the Ayatollah Khomeini saying in his sermons that the fate of Iran should never be allowed to be decided by women.[131] In 1963 and 1964, nationwide demonstrations against Mohammad Reza's rule took place all over Iran, with the centre of the unrest being the holy city of Qom.[132] Students studying to be imams at Qom were most active in the protests, and Ayatollah Khomeini emerged as one of the leaders, giving sermons calling for the Shah's overthrow.[132] At least 200 people were killed, with the police throwing some students to their deaths from high buildings, and Khomeini was exiled to Iraq in 4 October 1965.[133]

The second attempt on the Shah's life occurred on 10 April 1965.[134] A soldier named Reza Shamsabadi shot his way through the Marble Palace. The assassin was killed before he reached the royal quarters, but two civilian guards died protecting the Shah.[135]

Conflict with communists

[edit]According to Vladimir Kuzichkin, a former KGB officer who defected to MI-6, the Soviet Union also targeted the Shah. The Soviets tried to use a TV remote control to detonate a bomb-laden Volkswagen Beetle; the TV remote failed to function.[136] A high-ranking Romanian defector, Ion Mihai Pacepa, also supported this claim, asserting that he had been the target of various assassination attempts by Soviet agents for many years.[137]

Pahlavi's court

[edit]

Mohammad Reza's third and final wife was Farah Diba (born 14 October 1938), the only child of Sohrab Diba, a captain in the Imperial Iranian Army (son of an Iranian ambassador to the Romanov Court in St. Petersburg, Russia), and his wife, the former Farideh Ghotbi. They were married in 1959, and Queen Farah was crowned Shahbanu, or Empress, a title created especially for her in 1967. Previous royal consorts had been known as "Malakeh" (Arabic: Malika), or Queen. The couple remained together for 21 years, until the Shah's death. They had four children together:

- Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi (born 31 October 1960), heir to the now defunct Iranian throne. Reza Pahlavi is the founder and leader of National Council of Iran, a government in exile of Iran;

- Princess Farahnaz Pahlavi (born 12 March 1963);

- Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi (28 April 1966 – 4 January 2011);

- Princess Leila Pahlavi (27 March 1970 – 10 June 2001).

One of Mohammad Reza's favourite activities was watching films and his favourites were light French comedies and Hollywood action films, much to the disappointment of Farah who tried hard to interest him in more serious films.[138] Mohammad Reza was frequently unfaithful towards Farah, and his right-hand man Asadollah Alam regularly imported tall European women for "outings" with the Shah, though Alam's diary also mentions that if women from the "blue-eyed world" were not available, he would bring the Shah "local product".[139] Mohammad Reza had an insatiable appetite for sex, and Alam's diary has the Shah constantly telling him he needed to have sex several times a day, every day, or otherwise he would fall into depression.[139] When Farah found out about his affairs in 1973, Alam blamed the prime minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda while the Shah thought it was the KGB. Milani noted that neither admitted it was the Shah's "crass infidelities" that caused this issue.[139] Milani further wrote that "Alam, in his most destructive moments of sycophancy, reassured the Shah—or his "master" as he calls him—that the country was prosperous and no one begrudged the King a bit of fun". He also had a passion for automobiles and aeroplanes, and by the middle 1970s, the Shah had amassed one of the world's largest collection of luxury cars and planes.[140] His visits to the West were invariably the occasions for major protests by the Confederation of Iranian Students, an umbrella group of far-left Iranian university students studying abroad, and Mohammad Reza had one of the world's largest security details as he lived in constant fear of assassination.[127]

Milani described Mohammad Reza's court as open and tolerant, noting that his and Farah's two favourite interior designers, Keyvan Khosrovani and Bijan Saffari, were openly gay, and were not penalised for their sexual orientation with Khosrovani often giving advice to the Shah about how to dress.[141] Milani noted the close connection between architecture and power in Iran as architecture is the "poetry of power" in Iran.[141] In this sense, the Niavaran Palace, with its mixture of modernist style, heavily influenced by current French styles and traditional Persian style, reflected Mohammad Reza's personality.[142] Mohammad Reza was a Francophile whose court had a decidedly French ambiance to it.[143]

Mohammad Reza commissioned a documentary from the French filmmaker Albert Lamorisse meant to glorify Iran under his rule. But he was annoyed that the film focused only on Iran's past, writing to Lamorisse there were no modern buildings in his film, which he charged made Iran look "backward".[138] Mohammad Reza's office was functional whose ceilings and walls were decorated with Qajar art.[144] Farah began collecting modern art and by the early 1970s owned works by Picasso, Gauguin, Chagall, and Braque, which added to the modernist feel of the Niavaran Palace.[143]

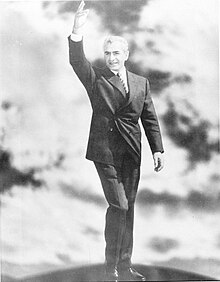

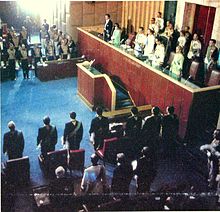

Imperial coronation

[edit]On 26 October 1967, twenty-six years into his reign as Shah ("King"), he took the ancient title Shāhanshāh ("Emperor" or "King of Kings") in a lavish coronation ceremony held in Tehran. He said that he chose to wait until this moment to assume the title because in his own opinion he "did not deserve it" up until then; he is also recorded as saying that there was "no honour in being Emperor of a poor country" (which he viewed Iran as being until that time).[145]

2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire

[edit]

As part of his efforts to modernise Iran and give the Iranian people a non-Islamic identity, Mohammad Reza quite consciously started to celebrate Iranian history before the Arab conquest with a special focus on the Achaemenid period.[146] In October 1971, he marked the anniversary of 2,500 years of continuous Persian monarchy since the founding of the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great. Concurrent with this celebration, Mohammad Reza changed the benchmark of the Iranian calendar from the Hijrah to the beginning of the First Persian Empire, measured from Cyrus the Great's coronation.[147]

At the celebration at Persepolis in 1971, the Shah had an elaborate fireworks show intended to send a dual message; that Iran was still faithful to its ancient traditions and that Iran had transcended its past to become a modern nation, that Iran was not "stuck in the past", but as a nation that embraced modernity had chosen to be faithful to its past.[148] The message was further reinforced the next day when the "Parade of Persian History" was performed at Persepolis when 6,000 soldiers dressed in the uniforms of every dynasty from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis marched past Mohammad Reza in a grand parade that many contemporaries remarked "surpassed in sheer spectacle the most florid celluloid imaginations of Hollywood epics".[148] To complete the message, Mohammad Reza finished off the celebrations by opening a brand new museum in Tehran, the Shahyad Aryamehr, that was housed in a very modernistic building and attended another parade in the newly opened Aryamehr Stadium, intended to give a message of "compressed time" between antiquity and modernity.[148] A brochure put up by the Celebration Committee explicitly stated the message: "Only when change is extremely rapid, and the past ten years have proved to be so, does the past attain new and unsuspected values worth cultivating", going on to say the celebrations were held because "Iran has begun to feel confident of its modernization".[148] Milani noted it was a sign of the liberalization of the middle years of Mohammad Reza's reign that Hussein Amanat, the architect who designed the Shahyad was a young Baha'i from a middle-class family who did not belong to the "thousand families" that traditionally dominated Iran, writing that only in this moment in Iranian history such a thing was possible.[149]

Role at OPEC

[edit]1973 Arab–Israeli War

[edit]Prior to the 1973 oil embargo Iran spearheaded OPEC's aim for higher oil prices. When raising oil prices Iran would point out the rising inflation as a means to justify the price increases.[150] In the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, Arab states employed an oil embargo in 1973 against Western nations. Although the Shah declared neutrality, he sought to exploit the lack of crude oil supply to Iran's benefit. The Shah held a meeting of Persian Gulf oil producers declaring they should double the price of oil for the second time in a year. The price hike resulted in an “oil shock” that crippled Western economies while Iran saw a rapid growth of oil revenues. Iranian oil incomes doubled to $4.6 billion in 1973–1974 and spiked to $17.8 billion in the following year. As a result, the Shah had established himself as the dominant figure of OPEC, having control over oil prices and production. Iran experienced an economic growth rate of 33% in 1973 and 40% the next year, and GNI expanded 50% in the next year.[151]

The Shah directed the growth in oil revenues back into the domestic economy. Elementary school education was made free and mandatory, major investments were made in the military, and in 1974, 16 billion dollars were spent on building new schools and hospitals. The Shah's oil coup signaled that the United States had lost the ability to influence Iranian foreign and economic policy.[151] Under the Shah, Iran dominated OPEC and middle eastern oil exports.[152]

Nationalist Iran

[edit]By the 19th century, the Persian word Vatan began to refer to a national homeland by many intellectuals in Iran. The education system was largely controlled by Shiite clergy who utilized a Maktab system in which open political discussion of modernization was prevented. However, a number of scholarly intellectuals including Mirzā FathʿAli Ākhundzādeh, Mirzā Āqā Khān Kermāni and Mirzā Malkam Khān began to criticize Islam's role in public life while promoting a secular identity for Iran. Over time studies of Iran's glorious history and present reality of a declined Qajar period led many to question what led to Iran's decline.[153] Ultimately Iranian history was categorized into two periods pre-Islamic and Islamic. Iran's pre-Islamic period was seen as prosperous while the Arab invasions were seen as, ‘a political catastrophe that pummelled the superior Iranian civilization under its hoof.’[154] Therefore, as a result of the growing number of Iranian intellectuals in the 1800s, the Ancient Persian Empire symbolized modernity and originality, while the Islamic period brought by Arab invasions brought Iran to a period of backwardness.[153]

Ultimately these revelations in Iran would lead to the rise of Aryan nationalism in Iran and the perception of an 'intellectual awakening', as described by Homa Katouzian. In Europe, many concepts of Aryan Nationalism were directed at the anti-Jewish sentiment. In contrast, Iran's Aryan nationalism was deeply rooted in Persian history and became synonymous with an anti-Arab sentiment instead. Furthermore, the Achaemenid and Sasanian periods were perceived as the real Persia, a Persia which commanded the respect of the world and was void of foreign culture before the Arab invasions.[153]

Thus, under the Pahlavi state, these ideas of Aryan and pre-Islamic Iranian nationalism continued with the rise of Reza Shah. Under the last Shah, the tomb of Cyrus the Great was established as a significant site for all Iranians. The Mission for My Country, written by the Shah, described Cyrus as ‘one of the most dynamic men in history’ and that ‘wherever Cyrus conquered, he would pardon the very people who had fought him, treat them well, and keep them in their former posts ... While Iran at the time knew nothing of democratic political institutions, Cyrus nevertheless demonstrated some of the qualities which provide the strength of the great modern democracies’. The Cyrus Cylinder also became an important cultural symbol and Pahlavi successfully popularized the decree as an ancient declaration of human rights.[153] The Shah employed titles like Āryāmehr and Shāhanshāh in order to emphasize Iranian supremacy and the kings of Iran.[155]

The Shah continued on with his father's ideas of Iranian nationalism concluding Arabs as the utmost other. Nationalist narratives which were widely accepted by a majority of Iranians portraying Arabs as hostile to Pahlavi's revival of ‘modern’ and ‘authentic’ Iran.[156]

Economic growth

[edit]

In the 1970s, Iran had an economic growth rate equal to that of South Korea, Turkey and Taiwan, and Western journalists all regularly predicted that Iran would become a First World nation within the next generation.[157] Significantly, a "reverse brain drain" had begun with Iranians who had been educated in the West returning home to take up positions in government and business.[158] The firm of Iran National ran by the Khayami brothers had become by 1978 the largest automobile manufacturer in the Middle East producing 136,000 cars every year while employing 12,000 people in Mashhad.[158] Mohammad Reza had strong étatist tendencies and was deeply involved in the economy, with his economic policies bearing a strong resemblance to the same étatist policies being pursued simultaneously by General Park Chung-hee in South Korea. Mohammad Reza considered himself to be a socialist, saying he was "more socialist and revolutionary than anyone".[158] Reflecting his self-proclaimed socialist tendencies, although unions were illegal, the Shah brought in labour laws that were "surprisingly fair to workers".[159] Iran in the 1960s and 70s was a tolerant place for the Jewish minority with one Iranian Jew, David Menasheri, remembering that Mohammad Reza's reign was the "golden age" for Iranian Jews when they were equals, and when the Iranian Jewish community was one of the wealthiest Jewish communities in the world. The Baha'i minority also did well after the bout of persecution in the mid-1950s ended with several Baha'i families rising to prominence in the world of Iranian business.[160]

Under his reign, Iran experienced over a decade of double-digit GDP growth coupled with major investments in military and infrastructure.[161]

The Shah's first economic plan was geared towards large infrastructure projects and improving the agricultural sector which led to the development of many major dams particularly in Karaj, Safīdrūd, and Dez. The next economic plan was directed and characterized by an expansion in the credit and monetary policy of a nation which resulted in a rapid expansion of Iran's private sector, particularly construction. From the period 1955–1959, real gross fixed capital formation in the private sector saw an average annual increase of 39.3%.[162] The private sector credit rose by 46 percent in 1957, 61 percent in 1958, and 32 percent in 1959 (Central Bank of Iran, Annual Report, 1960 and 1961). By 1963, the Shah had begun a redistribution of land offering compensation to landlords valued on previous tax assessments, and the land obtained by the government was then sold on favorable terms to Iranian peasants.[163] The Shah also initiated the nationalization of forests and pastures, female suffrage, profit-sharing for industrial workers, privatization of state industries, and formation of literacy corps. These developments marked a turning point in Iranian history as the nation prepared to embark on a rapid and aggressive industrialization process.[162]

1963–1978 represented the longest period of sustained growth in per capita real income the Iranian economy ever experienced. During the 1963–77 period gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by an average annual rate of 10.5% with an annual population growth rate of around 2.7% placing Iran as one of the fasted growing economies in the world. Iran's GDP per capita was $170 in 1963 and rose to $2,060 by 1977. The growth was not just a result of increased oil revenues. In fact, the non-oil GDPs grew by an average annual rate of 11.5 percent, which was higher than the average annual rate of growth experienced in oil revenues. By the fifth economic planning, oil GDP rose to 15.3% strongly outpacing growth rates in oil revenue which only saw .5% growth. From 1963 to 1977 the industrial and the service sectors experienced annual growth rates of 15.0 and 14.3 percent, respectively. The manufacturing of cars, television sets, refrigerators, and other household goods increased substantially in Iran. For instance, over the small period of 1969 to 1977, the number of private cars produced in Iran increased steadily from 29,000 to 132,000 and the number of television sets produced rose from 73,000 in 1969 to 352,000 in 1975.[162]

The growth of industrial sectors in Iran led to substantial urbanization of the country. The extent of urbanization rose from 31 percent in 1956 to 49 percent in 1978. By the mid-1970s Iran's national debt was paid off, turning the nation from a debtor to a creditor nation. The balances on the nation's account for the 1959–78 period actually resulted in a surplus of funds of approximately $15.17 billion. The Shah's fifth five-year economic plan sought to achieve a reduction in foreign imports through the use of higher tariffs on consumer goods, preferential bank loans to the industrialists, maintenance of an overvalued rial, and food subsidies in urban areas. These developments led to the development of a new large industrialist class in Iran and the nation's industrial structure was extremely insulated from threats of foreign competition.[162]

In 1976, Iran saw its largest-ever GDP uptick, thanks in large part to the Shah's economic policies. According to the World Bank, when valued in 2010 dollars, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi improved the country's per-capita GDP to $10,261, the highest at any point in Iran's history.[164]

According to economist Fereydoun Khavand, “During these 15 years, the average annual growth rate of the country fluctuated above 10%. The total volume of Iran's economy increased nearly fivefold during this period. In contrast, during the past 40 years, Iran's average annual economic growth rate has been only about two percent. Considering the growth rate of Iran's population in the post-revolution period, the average per capita growth rate of Iran in the last 40 years is estimated between zero percent and half a percent. Among the main factors hindering the growth rate in Iran are a lack of a favorable business environment, severe investment weakness, very low levels of productivity, and constant tension in the country's regional and global relations.”[165]

Many European, American, and Japanese investment firms sought business ventures and to open up headquarters in Iran. According to one American investment banker:

"They are now dependent on Western technology, but what happens when they produce and export steel and copper, when they reduce their agricultural problems? They'll eat everybody else in the Middle East alive.”[166]

Relationship with the Western world

[edit]By the 1960s and 1970s, Iranian oil revenues experienced rapid growth. By the mid-1960s Iran saw "weakened U.S. influence in Iranian politics" and a strengthening in the power of the Iranian state. According to Homa Katouzian, the perception that the US was the instructor of the Shah's regime due to their support for the 1953 coup contradicted the reality that "its real influence" in domestic Iranian politics and policy "declined considerably".[167] In 1973 the Shah initiated an oil price hike with his control of OPEC further demonstrating the US no longer had influence over Iranian foreign and economic policies.[151] In response to American media outlets critical of him, the Shah claimed that Iran's oil price hikes did little to contribute to the rising inflation in the United States. Pahlavi also implied criticism of the US for not taking the lead on anti-communist efforts.[168]

In 1974 during the oil crisis, the Shah began an atomic nuclear energy policy prompting US Trade Administrator William E. Simon to denounce the Shah as a "nut." In response, US President Nixon publicly apologized to the Shah through a letter in order to disassociate the president and the United States from the statement. Simon's statement illustrated the growing American tensions with Iran over the Shah's raising of oil prices. Nixon's apology covered up the reality that the Shah's ambitions to become the leader in the Persian Gulf Area and the Indian Ocean basin was placing a serious strain on his relationship with the United States, particularly as India had tested its first atomic bomb in May 1974.[169]

Many critics labeled the Shah as a Western and American "puppet", an accusation that has been disproven as unfounded by contemporary scholars due to the Shah's strong regional and nationalist ambitions which often led Tehran to disputes with its Western allies.[170] In particular, the Carter administration which took control of the White House in 1977 saw the Shah as a troublesome ally and sought change in Iran's political system.[171]

By the 1970s, the Shah had become a strongman. His power had dramatically increased both in Iran and internationally, and on the tenth anniversary of the White Revolution, he challenged The Consortium Agreement of 1954 and terminated the agreement after negotiations with the oil consortium resulting in the establishment of 1973 Sale and Purchase Agreement.[172][173]

Khomeini accused the Shah of false rumors and employed Soviet methods of deception. The accusations were amplified by international media outlets which widely propagated the information and protests were widely shown on Iranian televisions.[174]

Many Iranian students studied across Western Europe and the United States where ideas of liberalism, democracy, and counterculture flourished. Among left-leaning Westerners, the Shah's reign was seen as equivalent to that of right-wing hate figures. Western anti-Shah fervor broadcast by European and American media outlets was ultimately adopted by Iranian students and intellectuals studying the West who accused the shah of Westoxification when it was the students themselves who were adopting Western liberalism they experienced during their studies. These Western ideas of liberalism resulted in utopian visions for revolution and social change. In turn, the Shah criticized Western democracies and equated them to chaos. Furthermore, the Shah chastised Americans and Europeans as being "lazy," and "lacking discipline," and criticized their student radicalism as being caused by Western decline. President Nixon expressed his concern to the Shah that Iranian students in the United States would similarly become radicalized, asking the Shah:[175]

“Are your students infected?” and “Can you do anything?”

Foreign relations and policies

[edit]France

[edit]

In 1961, the Francophile Mohammad Reza visited Paris to meet his favourite leader, General Charles de Gaulle of France.[176] Mohammad Reza saw height as the measure of a man and a woman (the Shah had a marked preference for tall women) and the 6 feet 5 inches (1.96 m) de Gaulle was his most admired leader. Mohammad Reza loved to be compared to his "ego ideal" of General de Gaulle, and his courtiers constantly flattered him by calling him Iran's de Gaulle.[176] During the French trip, Queen Farah, who shared her husband's love of French culture and language, befriended the culture minister André Malraux, who arranged for the exchange of cultural artifacts between French and Iranian museums and art galleries, a policy that remained a key component of Iran's cultural diplomacy until 1979.[177] Many of the legitimising devices of the regime such as the constant use of referendums were modelled after de Gaulle's regime.[177] Intense Francophiles, Mohammad Reza and Farah preferred to speak French rather than Persian to their children.[178] Mohammad Reza built the Niavaran Palace which took up 840 square metres (9,000 sq ft) and whose style was a blend of Persian and French architecture.[179]

United States

[edit]The Shah's diplomatic foundation was the United States' guarantee that it would protect his regime, enabling him to stand up to larger enemies. While the arrangement did not preclude other partnerships and treaties, it helped to provide a somewhat stable environment in which Mohammad Reza could implement his reforms. Another factor guiding Mohammad Reza in his foreign policy was his wish for financial stability, which required strong diplomatic ties. A third factor was his wish to present Iran as a prosperous and powerful nation; this fuelled his domestic policy of Westernisation and reform. A final component was his promise that communism could be halted at Iran's border if his monarchy was preserved. By 1977, the country's treasury, the Shah's autocracy, and his strategic alliances seemed to form a protective layer around Iran.[180]

Although the U.S. was responsible for putting the Shah in power, he did not always act as a close American ally. In the early 1960s, when the State Department's Policy Planning Staff that included William R. Polk encouraged the Shah to distribute Iran's growing revenues more equitably, slow the rush toward militarisation, and open the government to political processes, he became furious and identified Polk as "the principal enemy of his regime." In July 1964, the Shah, Turkish President Cemal Gürsel, and Pakistani President Ayub Khan announced in Istanbul the establishment of the Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD) organisation to promote joint transportation and economic projects. It also envisioned Afghanistan's joining at some time in the future. The Shah was the first regional leader to grant de facto recognition to Israel.[181] When interviewed on 60 Minutes by reporter Mike Wallace, he criticised American Jews for their presumed control over U.S. media and finance, saying that The New York Times and The Washington Post were so pro-Israel in their coverage that it was a disservice to Israel's own interests. He also said that the Palestinians were "bully[ing] the world" through "terrorism and blackmail".[182] The Shah's remarks on the alleged Jewish lobby are widely believed to have been intended to pacify the Shah's Arab critics, and in any case, bilateral relations between Iran and Israel were not adversely affected.[181] In a 1967 memo to President Lyndon B. Johnson, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara wrote that "our sales [to Iran] have created about 1.4 million man-years of employment in the U.S. and over $1 billion in profits to American industry over the last five years," leading him to conclude that Iran was an arms market the United States could not do without.[183] In June 1965, after the Americans proved reluctant to sell Mohammad Reza some of the weapons he asked for, the Shah visited Moscow, where the Soviets agreed to sell some $110 million worth of weaponry; the threat of Iran pursuing the "Soviet option" caused the Americans to resume selling Iran weapons.[183] Additionally, British, French, and Italian arms firms were willing to sell Iran weapons, thus giving Mohammad Reza considerable leverage in his talks with the Americans, who sometimes worried that the Shah was buying more weapons than Iran needed or could handle.[183]

Arab countries

[edit]

Concerning the fate of Bahrain (which Britain had controlled since the 19th century, but which Iran claimed as its own territory) and three small Persian Gulf islands, the Shah negotiated an agreement with the British, which, by means of a public consensus, ultimately led to the independence of Bahrain (against the wishes of Iranian nationalists). In return, Iran took full control of Greater and Lesser Tunbs and Abu Musa in the Strait of Hormuz, three strategically sensitive islands which were claimed by the United Arab Emirates. During this period, the Shah sent one of his most trusted tribal men Sheikh Abdulkarim Al-Faisali and maintained cordial relations with the Persian Gulf states and established close diplomatic ties with Saudi Arabia. Mohammad Reza saw Iran as the natural dominant power in the Persian Gulf region, and tolerated no challenges to Iranian hegemony, a claim that was supported by a gargantuan arms-buying spree that started in the early 1960s.[184] Mohammad Reza supported the Yemeni royalists against republican forces in the Yemen Civil War (1962–70) and assisted the sultan of Oman in putting down a rebellion in Dhofar (1971). In 1971, Mohammad Reza told a journalist: "World events were such that we were compelled to accept the fact that sea adjoining the Oman Sea—I mean the Indian Ocean—does not recognise borders. As for Iran's security limits—I will not state how many kilometers we have in mind, but anyone who is acquainted with geography and the strategic situation, and especially with the potential air and sea forces, know what distances from Chah Bahar this limit can reach".[185]